“I hate the Grateful Dead.”

I used to say that a lot, for a long time. Sometimes I would draw out the word “hate” to emphasize my distaste: “I haaaaaaate the Grateful Dead.” The band seemed to be a separate entity from the other classic rock bands of the same era—The Stones, Zeppelin, Black Sabbath—whom I loved so much. I mostly thought of them as the soundtrack for people who hated having jobs and showering. My father—who is both well-groomed and gainfully employed—was a Dead fan and had seen them play Madison Square Garden in the early 80s, although he later admitted to me that he found the performance “boring.” Anything my dad was into was, in my opinion, as uncool as it gets.

It also seemed like everyone I knew who liked the Grateful Dead actually just liked doing drugs, which I assumed was the only reason they listened to the band at all. However, in recent years, I’ve made a concerted effort to stop caring about appearances. I stopped concerning myself with what others think is cool and began to enjoy things for what they are. That’s how I found myself flying to the desert in the middle of the summer to see what remains of the Grateful Dead perform in one of the most impressive audio-visual experiences I’ve ever had, housed in a high-tech orb.

I worked in record stores for a long time and used it as an opportunity to expand my musical knowledge beyond classic rock, indie, and hip-hop, which was all I really listened to at the time. I delved into country and jazz, buying Willie Nelson’s Red Headed Stranger and Thelonious Monk’s album with Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers. Throughout the workday, the shop’s employees would rotate album choices, and I would play stuff like Coltrane’s Blue Train, often to the dismay of my coworkers. My boss, on the other hand, would play the same bluegrass Dead covers album on repeat, which only deepened my resentment for the band. I came to dislike their songs without ever hearing the originals. When live bootlegs would play, the jams seemed to go on forever, boring me to tears. I didn’t listen so much as I waited for the songs to end so I could put on Herbie Hancock or Merle Haggard. I was convinced the Dead wasn’t for me and avoided the band and their fans like the plague.

Almost two decades later, the rise of Spotify made it easier to discover new music without committing to buying an album. One day, I noticed Europe ‘72 in my suggested albums feed and decided to give it a shot. I had always been intrigued by the album’s cover, which featured a cartoon of a boy in a rainbow afro wig smashing an ice cream cone into his forehead. Maybe it was my love for ice cream, but something about it appealed to me.

Upon first listen, I realized that a lot of the material was, as Garth Brooks once said, “country as a biscuit.” Songs like “Cumberland Blues,” “Brown Eyed Women,” and “Tennessee Jed” carried the melodies and themes of country music but with a hard rock edge. I was blown away by Jerry Garcia’s guitar solos, the funky drums of Bill Kreutzmann, the soulful blues of Pigpen, the unique bass lines of Phil Lesh, and whatever the hell Bob Weir was doing. Robert Hunter’s lyrics—vivid stories filled with characters like Jack Straw and Mr. Charlie—were unlike anything I’d heard from other bands. It was like listening to music that combined the best of country, jazz, and rock, paired with lyrics that read like a novelist’s prose.

From there, it was off to the races. My next stop was Cornell ‘77, the band’s legendary and much-heralded performance at the Ivy League institution of Ithaca. Even without Pigpen, the addition of Mickey Hart as an auxiliary percussionist gave the band a more dynamic sound. The album also featured covers of two of my all-time favorite country songs: Merle Haggard’s “Mama Tried” and Marty Robbins’ “El Paso.” The latter became as much Bob Weir’s signature as Robbins’, adding a new layer to the band’s already eclectic sound. Over the next year, I found myself diving deep into different live performances—Veneta ‘72, Nassau ‘90, Englishtown ‘77— I was fully hooked.

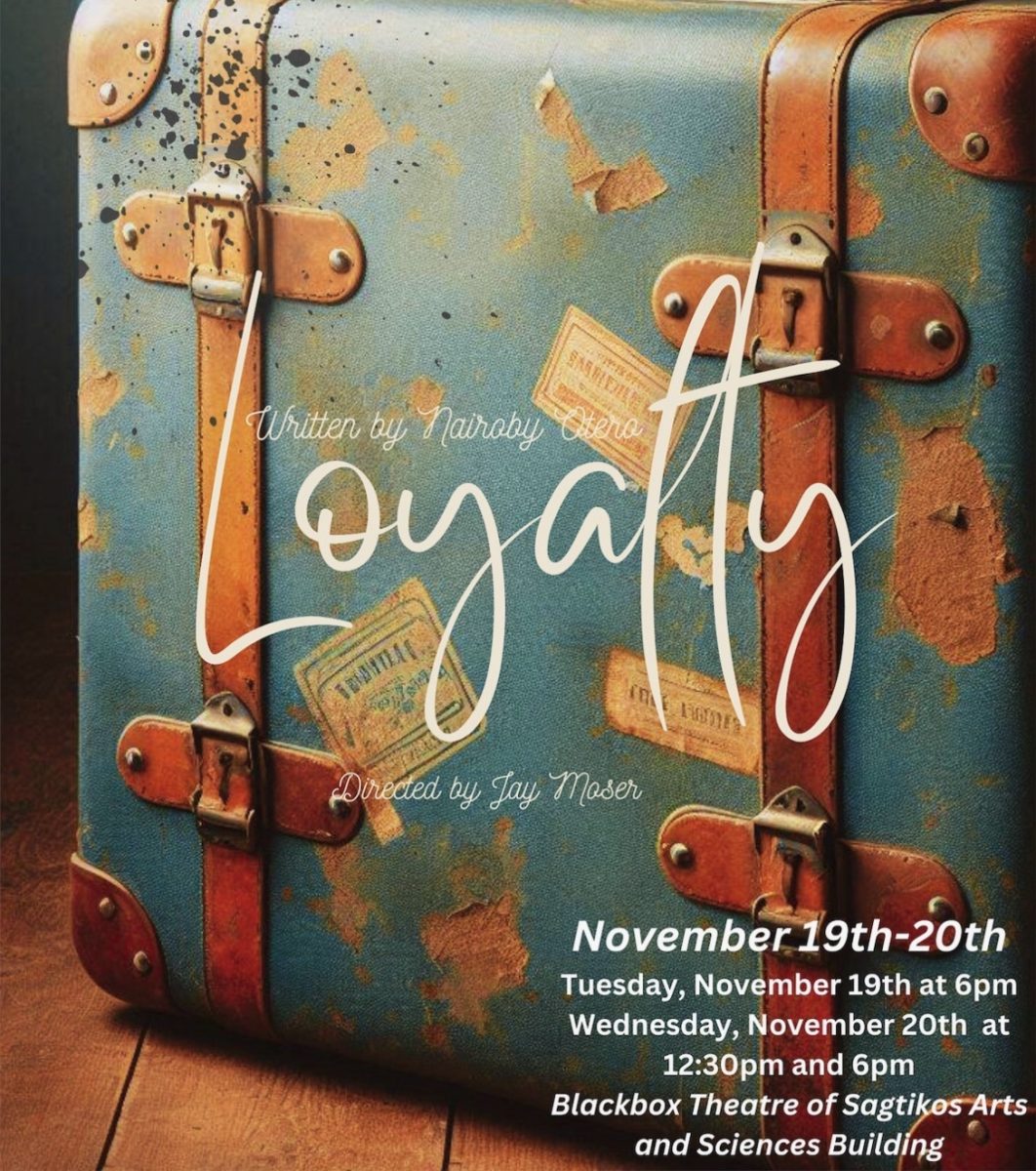

It all came to a head last summer when I flew out to see Dead & Company at the Sphere (though they just call it Sphere, without the definite article, which I think is dumb and refuse to comply) in Las Vegas. I’ve never flown anywhere just to see a band, but I had to take the chance to see the aged remains of my new favorite group play inside a futuristic space orb. By chance, John Mayer had cut his index finger on his fretting hand in a kitchen accident a week earlier. Undaunted, he played guitar with only three fingers, and you’d hardly notice a difference—undoubtedly the most impressive feat I’ve ever seen a guitarist accomplish. The band opened with “Iko Iko” and followed it with a mesmerizing half-hour rendition of “Eyes of the World,” while the Sphere’s screens made it feel like we were being launched into the far reaches of outer space. The whole experience was jaw-dropping, though I’ll admit I was slightly disappointed when I saw the following night’s setlist and found out I missed out on a “Dark Star > El Paso > Dark Star” sequence.

“Dark Star,” in particular, has become something of an obsession for me. For those in the know, it is more than just a song; it’s a continuous, evolving journey that transcends the boundaries of traditional music. As former Grateful Dead pianist Tom Constanten put it, “’Dark Star’ is going all the time. You don’t begin it so much as you enter it. You don’t end it so much as leave it.” Each performance taps into an ever-present flow of improvisation, where time and structure dissolve. Jerry’s guitar leads the band through shifting moods and cosmic soundscapes, blending rock, jazz, and psychedelia into something far greater than the sum of its parts. The sparse lyrics by Robert Hunter add to its mystique, creating a sense of wonder and space for interpretation. “Dark Star” is an immersive experience that rewards deep listening, where each version is a unique entry point into an infinite musical galaxy that’s always there, waiting to be explored. I love the song’s free-form structure, and I’ve been working my way through various versions of it, keeping a running list of my favorites. My current top pick is a from November 11, 1973, at Winterland in San Francisco, which clocks in at a respectable 35:40. I saw an internet comment describe it as “the thinking man’s ‘Dark Star.’” While I’m not sure exactly what that means, I appreciate the sentiment, nonetheless.

In the Sphere, watching the most mind-blowing visuals I’ve ever seen at a concert, I couldn’t help but the total 180 I had made. In reality, I had missed the point. The music—the sheer musicality, the storytelling, the experimentation—is what matters. Once I let go of worrying about what was “cool,” I was able to appreciate the Dead for what they really are: a brilliant, genre-defying band that I’ve come to love. As Bill Graham once said, “They’re not the best at what they do, they’re the only ones that do what they do.”