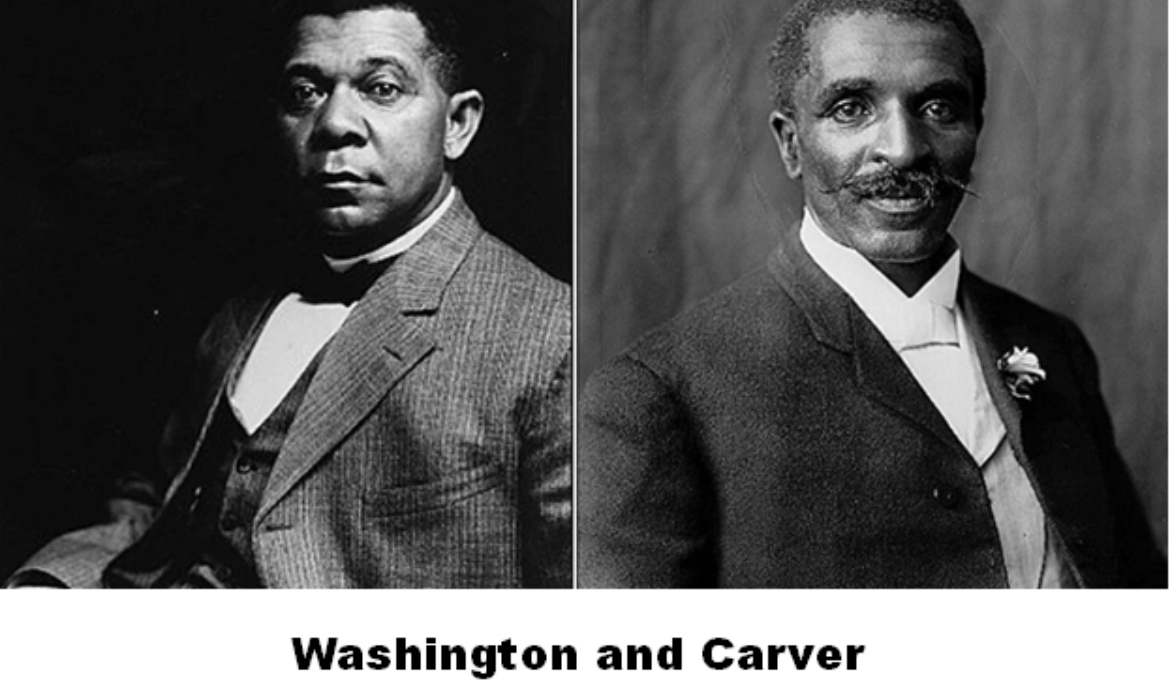

Booker T. Washington was born on a tobacco farm in Hale’s Ford, Virginia, year unknown (suggested perhaps 1856) to an enslaved mother and unknown White plantation owner. At some point after Washington was born, his mother married an enslaved man and the family settled in Maiden, West Virginia. There Booker worked in the salt mines and as a houseboy for a White woman who taught him to read and write. When time permitted, heattended a rural school for formerly enslaved people. In 1872 he attended the HamptonInstitute in Hampton, Virginia which provided formerly enslaved people, industrial educationand traditional subjects. After graduating, he continued his education at the Wayland Seminary in Washington, D.C., a college for freedmen.

In 1881 the founder of the Hampton Institute recommended Booker to head a newly planned college for African Americans in Tuskegee, Alabama. At its inception, the enrollment was 30, Booker, the only teacher, and they met in a shanty belonging to the United Methodist Church. As the enrollment and faculty increased, Washington purchased a former plantation and had its buildings constructed by the students and teachers using their industrial skills. The task of the increased faculty was to ready the men and women students to become teachers of their trades and share their knowledge in the southern rural areas. His belief for his race was that through the Tuskegee plan, students were provided the needed skills to be productive members of society. By so doing, African Americans would be more readily accepted by White Americans.

The Tuskegee plan had impressed many and he was invited to speak to an integrated audience at the 1895 Atlanta Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, Georgia, a first for an African American. At the end of the speech, he presented a metaphor of the hand: “In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.” The speech resulted in his gaining support in the Black communities of the South, and amongliberal Whites throughout the nation.

However, as the speech was publicized nationally, it became known as the Atlanta Compromise because some believed the metaphor implied the acceptance of segregation. W.E.B. Du Bois was one who disagreed with Booker T. Washington’s educational approach. Du Bois advocated for immediate full equality and integration and believed that Black schools should focus more on liberal arts and academic curriculum because liberal arts were required to develop an elite leadership.

(Ironically, after Washington’s death, historians learned that he was secretly making donations to fund legal challenges to Jim Crow laws. And after years of Du Bois criticizing Washington for his civil rights stance, in the mid 1930s, Du Bois commented to an astonished Black audience that “separate but equal” was an acceptable position for Blacks.)

Booker was apparently a convincing orator and conversationalist. By lobbying the West Virginia legislature, he helped develop the West Virginia Colored Institute later to become West Virginia State University. He was the first African American to dine at the White House at the invitation of Teddy Roosevelt. Hepresented at venues such as Carnegie Hall in New York City along with other guests, e.g.,Mark Twain. Because of his philosophy of the importance of slow moving change, and his charismatic nature, he built a national network of supporters including Black educators, journalists, White politicians, and philanthropists who consulted him regardingrace issues, and from whom he was given large donations.

In 1896 Booker T. Washington convinced George Washington Carver to join the faculty at Tuskegee as Director of Agriculture, a position he held for 47 years (1896-1943) and an impressive administrative decision on the part of Washington.

Carver was also born into slavery, but near the end of the Civil War. His brilliance in science and agriculture were recognized and resulted in his being a professor at what is now Iowa State University prior to his position at Tuskegee.

He, like Washington, believed in practical education to help African Americans become self-sufficient. To accomplish this, an important focus of the Tuskegee Agricultural Department was conducting research. He taught methods of crop rotation, and introduced alternative cash crops for farmers. Carver’s work regarding soil conservation and crop rotation were critical during the Great Depression. He is credited with educating generations of Black scientists, and teaching agricultural methods that would improve farming for Black farmers, thus improving their economic status.

Carver performed extensive research on crops such as peanuts, sweet potatoes, and soybeans and developed numerous uses for them. When Teddy Roosevelt visited Tuskegee, Washington asked Carver to introduce Roosevelt to the Institution. He impressed Roosevelt and later Calvin Coolidge, becoming agricultural advisor to both. In spite of the climate in 1921 with racism looming and the Ku Klux Klan re-emerging, he was invited to speak before Congress where he impressed lawmakers with his scientific knowledge.

While Carver was a student at Iowa State, he became acquainted with the family of Henry A. Wallace, FDR’s first Secretary of Agriculture. Wallace credits Carver for his lifelong passion of botany.

Henry Ford sought Carver’s advice in developing alternative energy sources to gasoline. During World War II, the U.S. government asked Carver and Ford to develop a soybean-based alternative to rubber. They produced a successful replacement using goldenrod. Because of their collaboration, Ford was able to develop a car with a lightweight body comprised in part from soybeans. As a result of his high esteem for Carver, Ford became a key financial backer of the Tuskegee Institute, underwriting many of Carver’s initiatives.

At Mahatma Gandhi’s request, Carver traveled to India to advise the vegetarian about nutrition. Carver convinced him of the importance of adding soy to his diet.

Carver’s scientific and innovative ideas and circle of influential supporters, greatly enhanced the reputation of Tuskegee Institution which resulted in the school gaining increased positive recognition.

Booker T. Washington died in 1915 having led Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institution for 34 years and whose campus at that point had 100 buildings, about 1,500 students, 200 faculty members, offered programs in 38 trades and professions, and had an endowment of 1.5 million equal to the current 2025 amount of approximately 500 million dollars. After his death, the Institute continued to flourish and in 1985 became Tuskegee University offering undergraduate and graduate degrees.

A few of Booker T. Washington’s many honors are being the first African-American to be commemorated on U.S postage stamps and a U.S. coin, granted honorary degrees from Harvard University and Dartmouth College, being the first African American having an ocean liner named for him, having his sculpture displayed at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C., and having a monument erected at Tuskegee University with the inscription:

He lifted the veil of ignorance from his people and pointed the way to progress through education and industry.

When George Washington Carver died in 1943, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed legislation establishing the George Washington Carver National Monument in Missouri (the first non-presidential national monument and the first to honor an African American).

Carver is buried next to Washington on the Tuskegee grounds. His epitaph reads, “He could have added fortune to fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honor in being helpful to the world.”

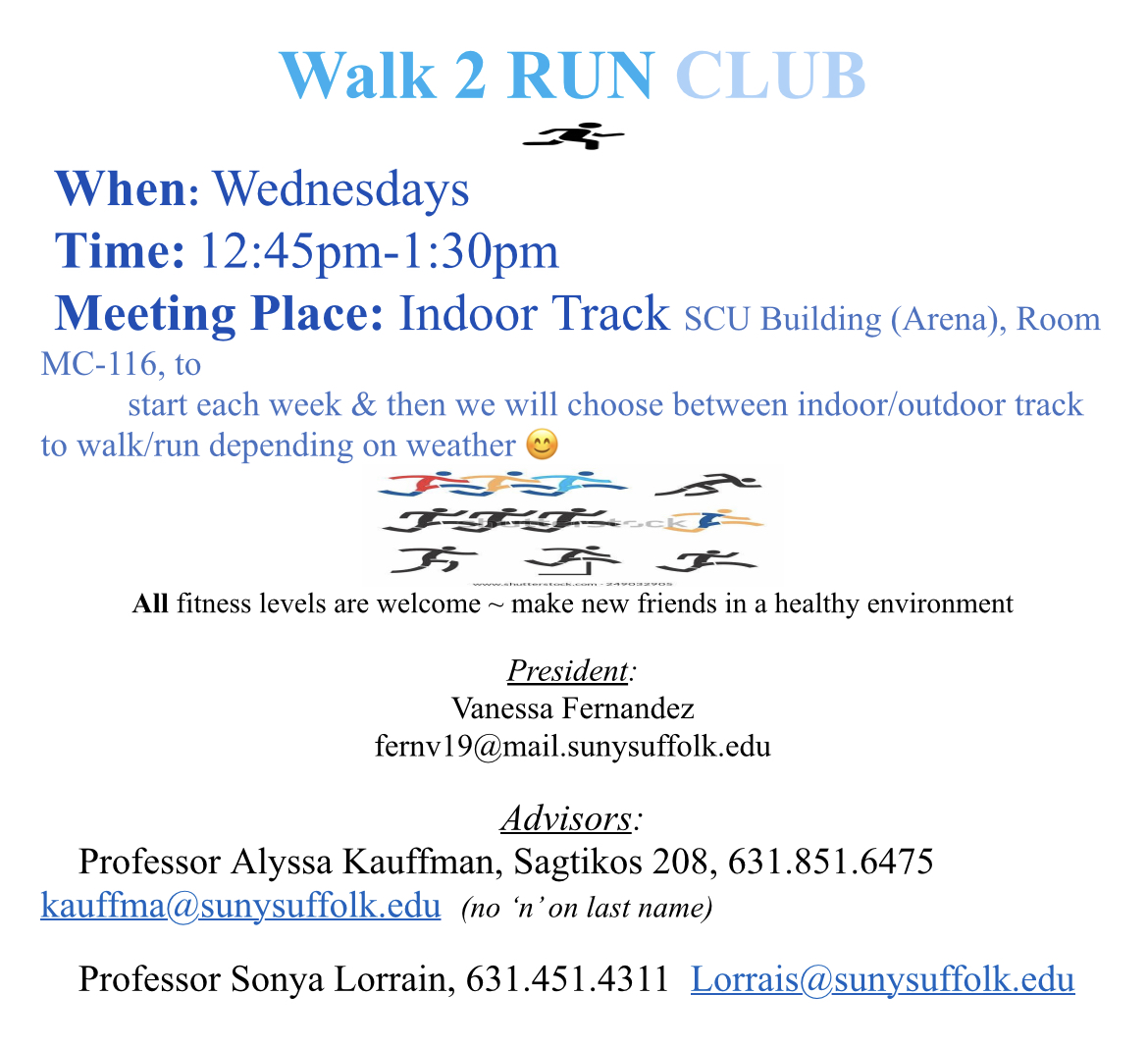

Please stop by the Grant Campus library and see the display about the people discussed. If this subject is of interest to you, our college libraries have sources referencing them and many other topics. Just ask a librarian.